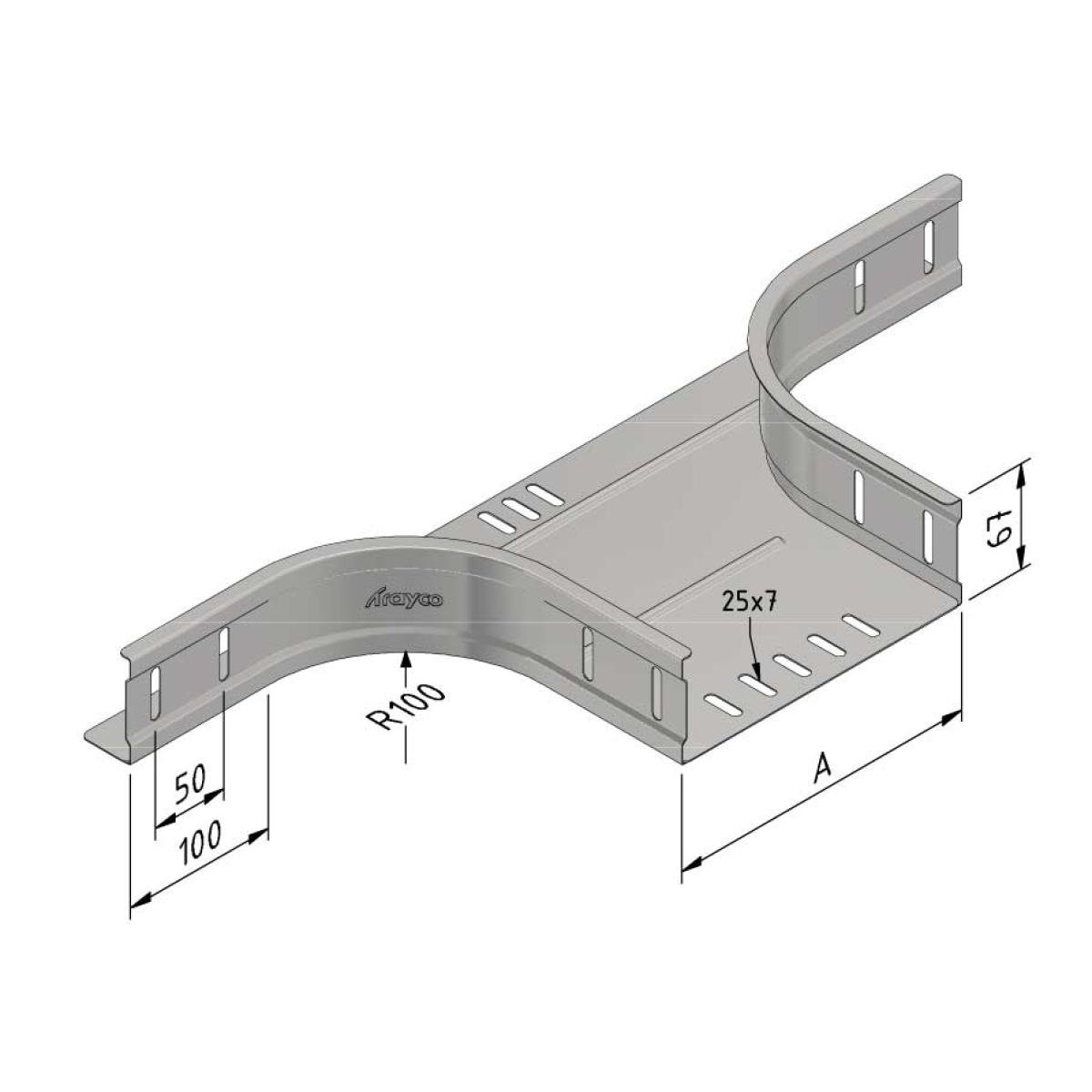

Cable Tray Branch

SS-CT-BR_

Cable Tray Branch

SS-CT-BR_

| SKU | Article code | Finishing | Dimension A | Packaging | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

13387 |

CT60-BR-100-SS316 |

SS316

|

100

|

1

|

Default

|

|

|

|

13389 |

CT60-BR-200-SS316 |

SS316

|

200

|

1

|

Default

|

|

|

|

13390 |

CT60-BR-300-SS316 |

SS316

|

300

|

1

|

Default

|

|